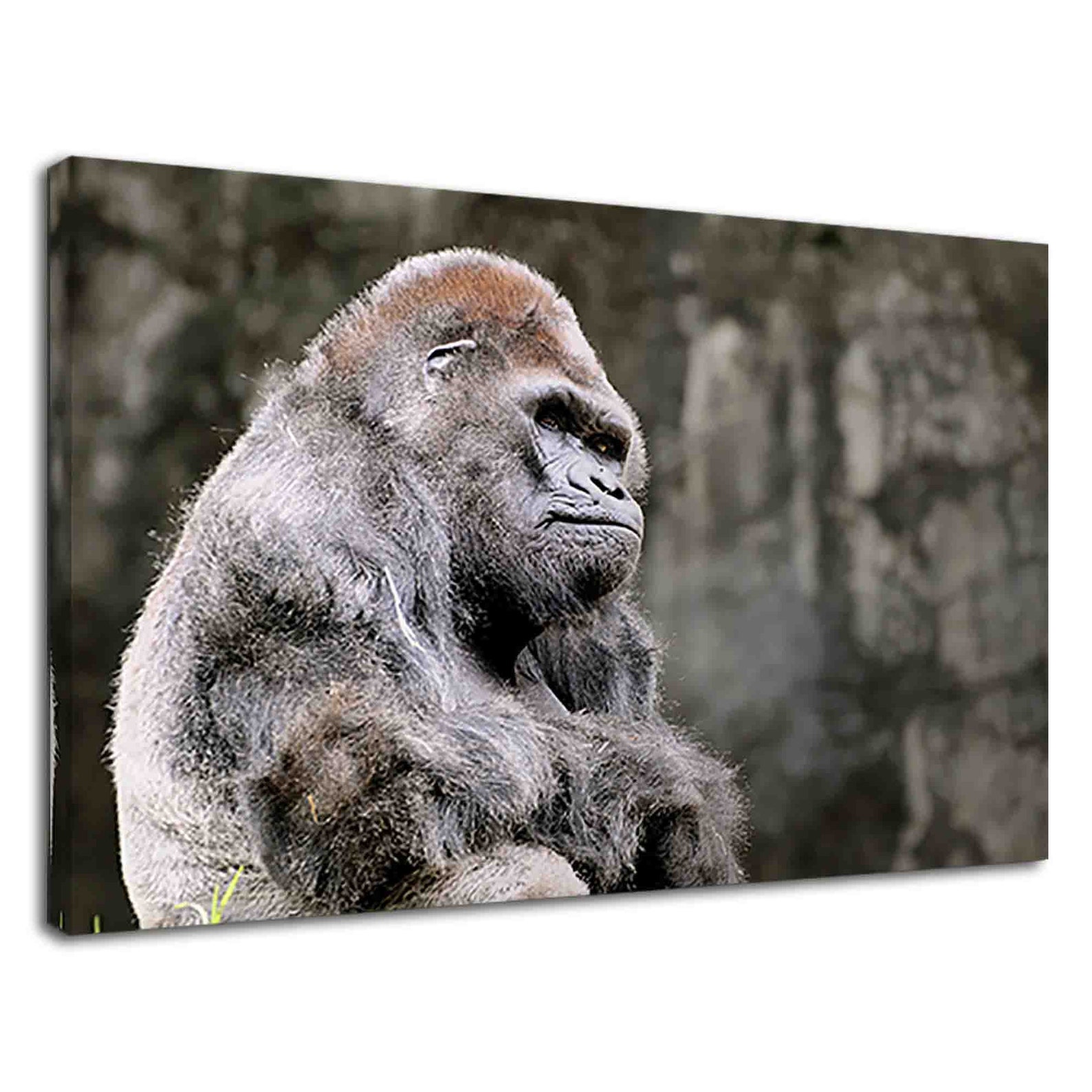

“But it turns out we should," Bergl added, “especially for social animals like gorillas.” “Normally when thinking about conservation, scientists focus on tangible, ecological issues like food availability, degradation of habitat, hunting by humans - rarely do we think about how an animal’s behavior and social structure can influence population size,” said Rich Bergl, a primatologist at the North Carolina Zoo, who also works on great ape conservation in Africa and was not involved in the paper. After teetering near the edge of extinction in the 1970s, the population has rebounded to just over 1,000 animals - considered to be “endangered” by scientists. Mountain gorillas have been a focus of intense research and conservation efforts in central Africa since the late 1960s. The frequency of gorilla family feuds was determined not by the total number of individuals, but by the number of family groups in a region, the study concluded. Males will fight to protect the females and infants in their group, and to acquire new females,” said Damien Caillaud, a behavioral ecologist at the University of California, Davis, and co-author of the new study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. “Encounters between groups can be violent. Some gorillas, especially infants, perished, which slowed population growth. Most often, dominant males called silverbacks led the fights.

Researchers who analyzed 50 years of demographic and behavioral data from Rwanda found that as the number of gorilla family groups living in a habitat increased, so did the number of violent clashes among them. These large vegetarian apes are generally peaceful – unless you’re a rival gorilla. Mountain gorillas spend most of their time sleeping, chomping leaves and wild celery stalks, and grooming each other’s fur with long, dexterous fingers. A crowded mountain can make silverbacks more violent, scientists say.

WASHINGTON - Gorillas are highly sociable animals – up to a point.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)